In late October, my wife and I embarked on our greatest adventure yet: a 17-day trip in Japan, spanning Tokyo, Kyoto, Nara, Osaka and Hiroshima, without guides or local contacts, armed with nothing but our maps and our wits.

We were no strangers to overseas travel, but we’d always traveled in group tours. The tour agencies handled accommodations, food and itinerary; we just had to show up and take in everything they had to offer. This year, we decided to do everything ourselves. Housing, transportation, electronics, communications, itinerary, route planning, and, most importantly, food.

After all, between the two of us, we are allergic to 40 different types of food.

Preparation

Cooking in Tokyo. This was supposed to be the plan…

Fortunately for us, we survived the trip. More than that, we thrived. Proper planning and preparation was critical to our success.

We spent 3 months planning the trip. We researched places to go, admission times, transportation methods and routes, admission fees, climate, and, most importantly, potential allergens.

We couldn’t count on being able to find allergen-free food in Japan. Modern Japanese cuisine makes heavy use of seafood, preserved foods and dairy, among other potential allergens. To ensure our safety, we decided to prepare meals in Japan.

We packed a pair of microwave egg cookers and a lunchbox cooker in our suitcases. The idea was to go shopping for food after arrival and prepare breakfast and dinner in our rented properties. In case we couldn’t find food for lunch, we packed plenty of snacks. In my case, I brought 10 nut bars from my personal stash..

For outside meals, we researched how to work around food allergies in Japan. Japanese law requires manufacturers to declare the presence of seven major food allergens, and recommends listing twenty other common allergens. Fortunately for us, some of our allergens fell into the mandatory list, such as shrimp and dairy.

Unfortunately, most of our other allergens were outside both lists.

We printed our allergen lists in English and Japanese, and prepared translated statements that listed what we could and could not eat. We downloaded Google Translate, whose camera mode would allow us to read Japanese ingredient lists and announcements in (allegedly) understandable English.

We thought we had everything figured out. Naturally, reality hit hard.

Best Laid Plans

Origin DIY onigiri and salad bar in Tokyo. Pictured left to right: allergens

Walking the streets of Japan, we quickly learned the difference between Japanese cuisine as prepared in Singapore and authentic Japanese cuisine in Japan. Japanese food is much, much, much saltier than in Singapore. Allergens are commonplace. And waitstaff are fallible — and don’t often speak English.

While exploring Tokyo Station one day, we discovered a Thai restaurant. It was well past lunchtime, we were hungry, and there were just two seats left. We squeezed ourselves into the last table and perused the menu.

At the top of the menu was chicken noodles. The waitress assured us that there was no seafood in it. We ordered two bowls, but I grew increasingly uneasy. This was, after all, a Thai restaurant, drawing inspiration from a cuisine grounded in peanuts and seafood, and since the menus listed allergens, I decided to double-check the menu with Google Translate.

Lo and behold, the noodles were cooked with shrimp.

The restaurant was a tiny hole in the wall. Even if we told the chef not to cook the food with shrimp or other seafood, there was no way to prevent cross-contamination. We decided to cancel our orders and leave the restaurant.

This was typical of our experiences in Japan. After entering a eatery, we browsed the menu, discovered the presence of allergens, and left. Our meals tended to drag much later than at home, for want of suitable meals.

On that particular day, we finally settled on sandwiches at Takashimaya. Egg sandwiches.

And shortly after lunch, we both had allergy attacks.

The ingredients list was free of allergens. However, next to the egg sandwiches were egg and tuna sandwiches and egg and pork cutlet sandwiches, both of which, for whatever reason, were prepared with shrimp. As far as I could tell, it was a case of cross-contamination.

Fortunately for us, it was a relatively minor episode, and we recovered within the hour. But it taught us to be extremely careful of what we ate.

While we had planned to cook meals in our dwellings, we were so busy in Tokyo we didn’t have time to prepare proper meals. We decided to start cooking proper meals once we reached Kyoto. On arrival, we discovered that Western Japan used a different electric standard from Tokyo. After the power sockets blew two of our universal adapters and a charging cable.

The following day, we purchased new adapter plugs designed for foreign appliances, for use throughout all of Japan. However the plugs operated at 125 volts while the lunchbox needed 240 volts. We decided it wasn’t safe to use the lunchbox.

Which meant the lunchbox turned to dead weight.

So much for our meal plans.

Improvise, Adapt, Overcome

Traditional Japanese meal in Kyoto, and the only fancy one we had. I’m allergic to everything but the rice and fish.

With our plans shot, we had to improvise solutions, adapt to the situation, and overcome the challenges in our way.

Bereft of our lunchbox cooker, we relied on our microwave egg cookers. A third of our breakfasts in Japan were either softboiled or scrambled eggs. Cheap, convenient and easy to clean up, they were our second preferred breakfast foods. The fact that we stayed near supermarkets made things easier; resupply was just five minutes away.

But that left lunch and dinner outside in cold, foreign cities.

Google Translate was a literal lifesaver. In addition to helping us converse with the locals, it allowed us to read and understand ingredient lists, and quickly make safe food choices. It proved especially useful in Osaka; among the cities we visited, it had the fewest signs and instructions in English.

When choosing eateries, we examined any sample food items on display. If there were too many instances of shellfish, nuts, or other allergens, we walked away. If there were notices warning that the restaurant could not guarantee immunity from cross-contamination, we walked. After finding a potential eatery, we asked for English menus. Many restaurants in tourist spots do offer such menus on request; for those that do not have English menus, we whipped out our phones and relied on Google Translate.

And if we found allergens, or if our instincts warned us against the food, we walked.

This happened far more often than not. Halfway through the trip, we figured that major establishments simply could not accommodate our needs. In the end, we relied on fast food.

MacDonald’s, Mos Burger and other Western fast food restaurants all around the world use (mostly) the same ingredients and cooking methods. If we could eat a meal at a fast food restaurant in Singapore, we could do the same in Japan. And that’s what happened. Every other day, we ate fast food — not out of choice, but necessity.

But where we could, we chose Japanese fast food.

Specifically, outlets that served traditional Japanese foods. Not the kind influenced by decades of exposure to Western tastes, but recipes and preparation methods that dated to the previous century.

We discovered noodle stands, tea houses and quaint ramen stores that prepared food with old-fashioned Japanese ingredients and cooking methods. No dairy, no nuts, no seafood, just honest noodles, clear broth, seaweed, eggs and meat. They were cheap, fast, tasty and, best of all, allergen-free. The only drawback was that many of these places were off the beaten path — but then, we were traveling on our own, with plenty of time and energy to explore.

To be sure, tachigui soba, or soba stands, could be found in many train stations. But they were too modern for our palates. With deep-fried battered meats and seafood on most of the menu, cross-contamination was guaranteed. We avoided these like the plague.

Despite our best efforts, we couldn’t always locate fast food outlets or traditional eating houses. But there were always convenience stores, or combini, around. No matter where we went, there was a 7/11, Family Mart or Lawson within walking distance. And with convenience stores came onigiri and yakitori.

Sure, there were plenty of snacks, bentos, buns and other foods on sale. But almost all of them contained some kind of allergen or other. Dairy, shellfish, pickled food, and other allergens were hidden in the most innocuous-looking foods: fried rice, egg onigiri, pork cutlet with rice, and so on.

After a long and careful survey, I determined I was not allergic to just three kinds of onigiri: salmon, seaweed and bonito flakes. It was still a far sight better than the yakitori; I could only eat grilled salted chicken, without sauce.

Onigiri dominated our lives in Japan, especially after leaving Tokyo. Onigiri for breakfast, onigiri for lunch, and sometimes onigiri for dinner too. Between half to two-thirds of our meals in Japan consisted solely of onigiri, interspaced with snacks. I mixed it up with yakitori sometimes, but they were only guaranteed to be available in the afternoon. And when that wasn’t enough, I reached for a nut bar.

I thought 10 nut bars were plenty for the trip. But coming from a tiny country, we had severely underestimated the size of every park, temple, palace and other place of interest we visited. Many times we found ourselves in the middle of nowhere without an eatery or combini in sight. Out came the nut bars again, and again, and again. Near the end, I had to exercise rationing, and made my supplies last until the final day.

My wife couldn’t stand the onigiri diet. She tried other convenience store foods, but soon discovered the burgers on sale were too oily for her — and she’s allergic to my nut bars. In the end, she snacked her way across Japan on Pocky and matcha ice cream. Which my system can’t tolerate.

A Choice of Evils

Tachigui soba in Kyoto. More importantly: allergen free.

To be clear, I am in no way recommending this diet.

Western-style fast food is a food of last resort. We ate it because we have no better alternatives, not because we truly want to. Our only consolation was that the quality of the food was consistently better than the fast food at home. The ingredients were fresher, the cooking methods superior, and the staff more courteous. That said… a burger is still a burger.

Homegrown Japanese fast foods get a pass. But only if the foods aren’t deep-fried, are free of allergens, and are hygienically prepared. The same goes for traditional Japanese restaurants that offer authentic Japanese cuisine. Sushi, ramen, soba and yakitori are nutritionally superior alternatives to Western-style burgers and fries, and sometimes are served much faster too. Should I return to Japan again, I’d prioritise identifying and locating such establishments.

Onigiri is, in no way, meant to replace meals for such a long period. They provide too little energy and too much salt. I had to guzzle green tea and mineral water every day to fight never-ending thirst. Near the end of the trip, I began suffering from bloating and gas, courtesy of the onigiri. Supplementation with yakitori can only go so far — and they are prepared with trace amounts of dairy. While the amount of dairy fell just below our allergen threshold, I made sure not to eat it every day to give my system time to recover.

Compounding matters was that we were on the go for ten to fourteen hours almost every day, taking breaks only occasionally. Whenever we moved to another city, we lugged between 25 to 35 kilos of luggage on foot for considerable distances. Further, Japan in autumn was much colder than we were used to, demanding more calories just to remain functional. Every day we burned lots of energy, but we weren’t eating enough to replace it. After returning from Japan, I discovered I had lost four kilos — of muscle.

Lessons Learned

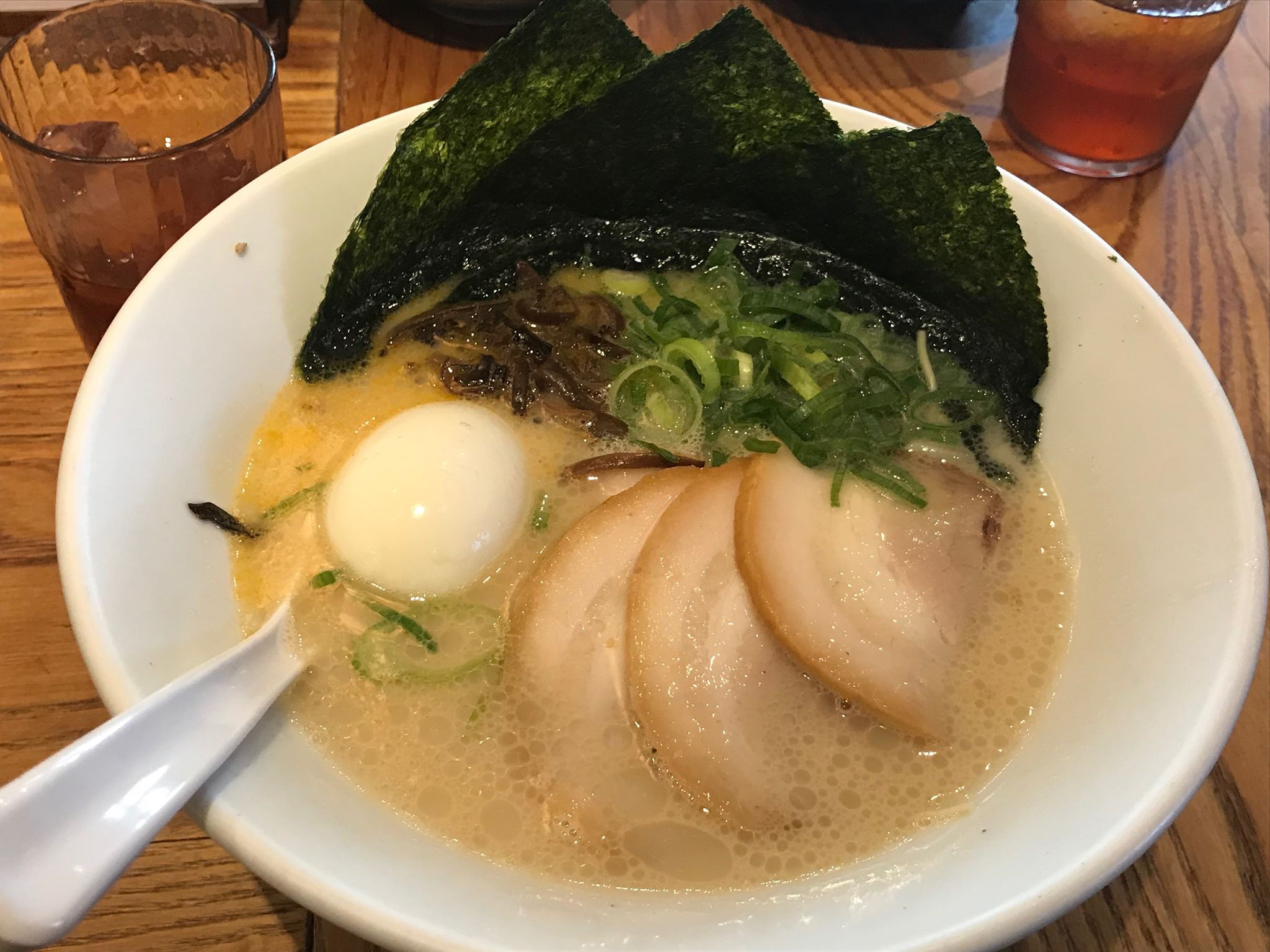

Ramen in Ikeda, Osaka. Paired with gyoza, rice and pork, the meal was completely allergen-free.

For all its drawbacks, the choice to me was simple. If you have to choose between constant allergic reactions or an onigiri diet, always pick the latter.

Despite the hassles we faced, I’d make the trip all over again. There is nothing in the world like immersing yourself in a completely foreign society and learning about their culture, language, history and patterns of life. But if I could, I’d do the following:

- Prepare plenty of hypoallergenic snacks, just in case

- Budget a lot more time for transition between places, between 45 to 90 minutes or longer

- Identify traditional eateries, convenience stores and supermarkets in the are

- Check electricity standards and prepare appropriate adapters

- Pack light, go far — but don’t discard important medicines, clothing and food supplies

Despite our allergens, our worst fears didn’t materialise. With sufficient planning, improvising on the go, and the power of almighty Google, we enjoyed our trip in Japan. Should we go on other overseas trips under similar conditions again, we wouldn’t just survive — we would thrive.

—

If you’d like to support my writing, check out my latest novel HAMMER OF THE WITCHES, and sign up for my mailing list here.

Leave a Reply