Singaporean students are the most creative students in the world. Singapore is also one of the least creative First World societies.

Both of these statements are simultaneously true.

I am one of Singapore’s most prolific and versatile writers. I have published 17 novels, 24 short stories and 2 non-fiction works. I also have 12 more unpublished manuscripts. My fiction spans many genres, from horror to xianxia to (anti-)LitRPG. I am also Singapore’s first Hugo- and Dragon Award nominated writer.

And chances are, if you’re Singaporean, you’ve only ever heard about me in a derogatory light.

Channel News Asia has published an article and an opinion piece saying that though Singaporeans are creative, they do not see themselves are creative. While the Confucian norms of downplaying one’s achievements and abilities probably plays a role, I think the situation is more nuanced than that.

After all, I am creative, and I do think of myself as a creative, but what does Singapore think?

Before we answer the question, let’s dive into the PISA study on creativity. To quote from page 18 of PISA’s Creative Thinking Framework:

[T]he PISA 2021 creative thinking assessment focuses on two broad thematic content areas: ‘creative expression’ and ‘knowledge creation and creative problem solving’. ‘Creative expression’ refers to instances where creative thinking is involved in communicating one’s inner world to others. This thematic content area is further divided into the domains of ‘written expression’ and ‘visual expression’. Originality, aesthetics, imagination, and affective intention and response largely characterise creative engagement in these domains. By contrast, creative engagement in ‘knowledge creation and creative problem-solving’ involves a more functional

employment of creative thinking that is related to the investigation of open questions or

problems (where there is no single solution). It is divided into the domains of ‘scientific

problem solving’ and ‘social problem solving’. In these domains, creative engagement is a

means to a ‘better end’, and it can thus be characterised by generating solutions that are

original, innovative, effective and efficient.

The vehicle for doing this is a standardised test. While standardised tests have their utility, fundamentally what they do is to assess the student‘s ability to solve problems in a structured environment.

This is the ‘Little C’ creativity mentioned in the CNA articles. A utilitarian, narrowly-focused form of creativity meant to address discrete, actionable problems within a well-defined context, producing incremental refinements on existing paradigms. While useful, by its very nature it cannot produce the epoch-defining creations that define ‘Big C’ creativity.

Singapore is engineered to strangle Big C creativity in the womb.

Big C creativity is not, and cannot, be limited to problem-solving. It is, quite literally, the ability to think differently. It is to dissent from what came before, to disagree with the edicts of established authorities, to step outside the existing framework, and to create a brand new way of doing things where none existed before.

During the medieval period in Europe, diseases were attributed to miasma, or ‘bad air’. Miasma theory persisted into the 1850s, and was used to explain the cholera outbreaks in London and Paris. Physician John Snow rejected the theory, arguing that cholera was spread by water. The leading lights of his time scoffed at the idea, claiming that any waterborne contaminants would have been diluted into harmlessness by the sheer volume of the Thames River. Undeterred, John Snow conducted his own investigation into cholera, and concluded that it was spread by waterworks companies that drew water from contaminated sources .

John Snow’s contribution to public health was made possible only by his doggedness and his willingness to challenge his fellow physicians—including doctors who stood far above him in the social hierarchy of the class-driven medical community at the time. England recognised and appreciated his defiance of both social norms and prevailing medical theory, and in time built a better model for public health.

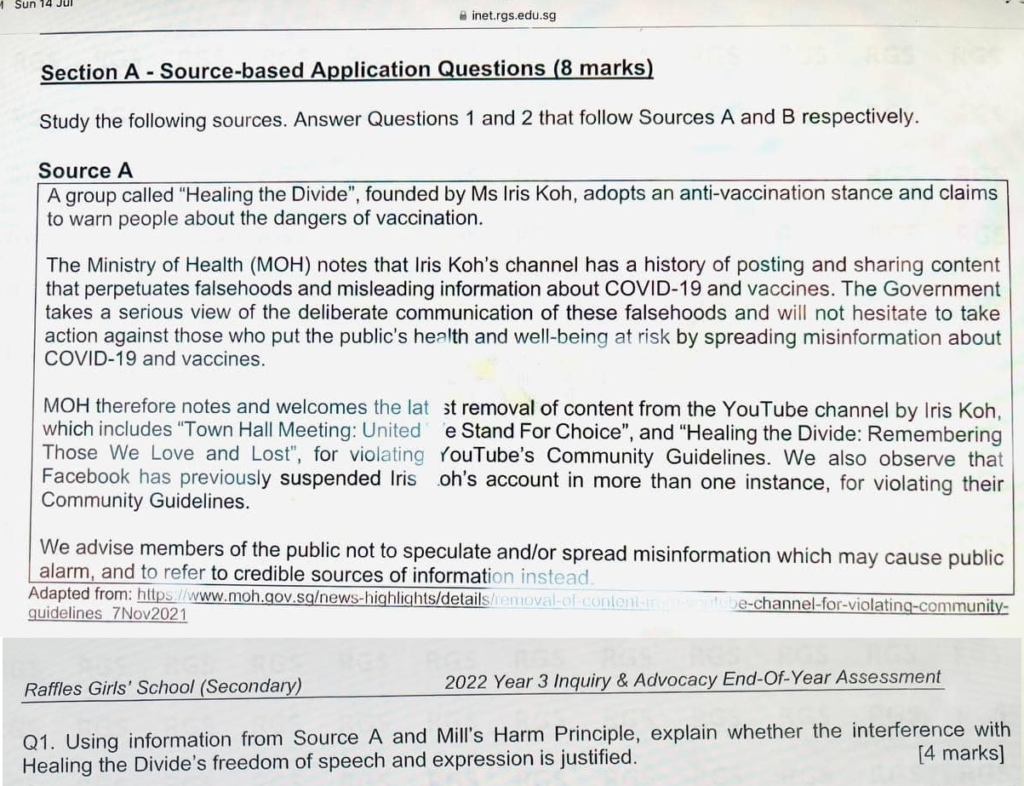

Contrast this with this examination question from Raffles Girl’s School:

As Chempost points out:

This is actually a ‘loaded question’ which is a complex question with a presupposition of an unverified assumption. It is a trick question often found in debates and social online arguments. It sets up an assumption that forces one to accept and thus entrapped to respond in accordance with the agenda of the questioner. An example is the Israel-Palestinian conflict. A typical question is “Israeli genocide has seen 30,000 Palestinians killed, mostly women and men. Why are you supporting Israel?”. The statement is unverified (how do you know 30,000 figure is correct? How do you know majority is women and children?) but it forces one to side with Palestinians, assuming one is not a genocidal maniac.

The presupposition in ‘Source A’ makes two assumptions. Firstly, the MOH’s opinion is assumed absolute. The reality is there are serious questions raised by medical experts. How is it wrong to bring contrarian views into the public domain? Note that Iris never assert her opinions, how could she, being a non-medical person. She was sharing other professional expert views. Secondly, YouTube and Facebook’s opaque grounds for suspension are assumed absolute. It is a fact these Big Techs use some AI to detect violations of their guidelines. It is also a fact these Big Techs are involved in political activism. Liberal partisanship bias have been built into their AI algorithms. Everyone, except fools, have woken up to this fact long time ago.

This is Singaporean creativity in a nutshell: you are free to answer the question as creatively as you like, so long as you give the answer they are looking for.

This is par the course for Singapore. The word of the authorities is absolute. Anyone who disagrees will face legal sanction, ranging from POFMA declarations to lawsuits to criminal charges.

It would take an extremely brave RGSian to declare that disagree with the official narrative. She would be extremely fortunate if nothing happened to her for doing so. How many secondary school girls would dare to take the risk of being the first to speak up?

It is easy to go along with the crowd. It is how you get your precious 8 marks in your year-defining exam. Why risk dropping out of a grade band, be called up by the principal, and be alienated by friends and family alike just to make a statement that no one will read?

Now extend this outside school life. Go along with the official narrative, and you will have the steady, reliable job that society prizes. Disagree, and you will ‘create trouble’ for yourself and everyone around you. You will be marked as a troublemaker, and only troublemakers like troublemakers.

Society cultivates what it incentivises and stamps out what it punishes, and Singapore incentivises conformity and punishes non-conformity. A society that does not allow its people to think differently is a society that embraces stagnation over creativity. Late Singaporean entrepreneur Sim Wong Hoo coined the term No U-Turn Syndrome to describe this situation. As described by Rice Media:

In other countries, the absence of a no U-turn sign denotes permission to make a U-turn. In Singapore, you can only do so when there is a U-turn sign, he wrote.

In other words, anything which happens to fall outside the rulebook is disallowed by default—not the best environment for anyone wanting to soar.

“How can we innovate when we need to obey rules to innovate? Innovate means to create things out of nothing, it means moving into uncharted territories where there are no rules.”

The article goes on to describe Sim’s challenges in founding Creative Technologies:

One of his early brushes with NUTS came when he and his team hunkered down to settle on a name for the company’s headquarters in 1997. The final moniker, Creative Resource, was rejected by the authorities, for the simple reason that ‘Resource’ wasn’t in a pre-approved list of names.

An indignant Sim fought back and appealed the decision. After what he described as a long process, he finally got what he wanted.

Over the years, he’d experienced NUTS time and again, from the authorities turning down reservist deferment requests for key staff members to his own employees sticking rigidly to existing workflows at the expense of good customer service.

Singapore encourages Little C creativity. Creativity that is small, focused, manageable, bound within a sociopolitically-acceptable framework. Big C creativity, the kind of creativity that creates a paradigm shift, threatens the existing order. The Establishment reflexively stamps it out.

When Singapore says its encourages creativity, it means the creativity of technocrats and bureaucrats. People who solve problems to uphold an existing framework. Not the creativity of pioneers, of people who forge a path into the unknown. Having framed itself as the builder, arbiter and enforcer of rules, the Establishment cannot tolerate those who do not obey the rules, or more accurately, their rules.

CNA’s opinion piece mentions jazz musician Jeremy Monteiro and actor Mark Lee, both of whom received accolades for their work. No doubt they are excellent creatives in their own right, but crucially, what they do is safe.

Jazz music doesn’t challenge the Establishment. Singaporean music rarely does, and so the technocrats see no problem with endorsing it. Mark Lee gained fame for comedic roles on television, and later diversified into hosting a variety of other programmes. These programmes were created by MediaCorp, and MediaCorp is Singapore’s state-owned public media conglomerate.

What they do is safe. But safety is the opposite of innovation.

Singaporeans are creative. Singapore is not. Individuals may be creative, but society stifles them. The only creatives society celebrates are those just creative enough to be outstanding, but not so outstanding that they threaten the guiderails that keep the herd in check. The result is a society of problem-solvers, not pioneers; iterators, not innovators; scholars, not sages.

As for myself, I ignored what everybody in Singapore had to say about fiction writing, and followed my vision. Here I am now, ready to take my work to the next level, writing the kind of stories no other Singaporean will dare to write.

It’s been a long, hard, uphill journey. Still I follow the beat of my drum, still I light a path into the unknown, still I lay down a trail behind me. This is the only road I can walk.

This is something the Establishment will never accept or understand.

No Singaporean will dare to publish a horror story like this.

Leave a Reply