When people think martial arts, they think of stunning strikes, intricate grappling and dynamic takedowns. Footwork is underappreciated in pop culture. But footwork makes these techniques work.

In some martial arts and sports, such as boxing and Muay Thai, it may be advantageous to absorb blows to less vital parts of the body in exchange for setting up a decisive blow. This is Rocky Balboa’s favourite strategy, letting his opponents wear themselves out and setting up opportunities to counterpunch. You can see this in his immortal fight against Ivan Drago.

In Filipino martial arts, when faced with an incoming blow, the preferred approach is to get out of the way. To understand why, simply replace Drago’s gloves with knives.

You can be as tough as Rocky, but mere flesh and bone isn’t going to stop steel and hardwood.

FMA originates from a weapon-based culture. The main assumption is that everyone is either armed or has ready access to a weapon. There is no way you can block a blade or stick with your body. You’ll just end up a bleeding, broken mess. Even if you don’t see a weapon, it doesn’t mean that the threat doesn’t have one—in the dark, against a small blade, you can’t tell if the threat is armed until your lifeblood gushes out on the floor.

You cannot afford to take a hit in FMA. The surest defence is to evade.

This is the guiding principle behind footwork. But it’s not the only reason to train footwork.

Footwork and Range

To understand footwork, we need to first understand range. There are three main ranges in Pekiti Tirsia Kali, my base art: largo, medio and corto. They are analogous to long, medium and short range.

At largo, you and your opponent are out of range. Neither of you can attack each other. Footwork in largo serves three purposes: place yourself in an advantageous position, bridge the distance and strike, or to escape before he and his buddies catch up to you.

In medio, you and your opponent can strike each other. This is the most dangerous zone in FMA. Assuming the two of you are equally skilled, there are three outcomes: you hit him, he hits you, or a mutual kill. Two out of three outcomes against your survival is not a winning proposition. In PTK, footwork at medio is designed to take you out of the danger zone: either out into largo, or deep into corto.

Corto is bad breath range. This is the realm of grapples, elbows and knees. PTK specialises In combat at this range: its name loosely translates into ‘chop up into little pieces’. In PTK, the goal of offensive footwork is to carry you safely into this position to finish off the threat. If the opponent resists you more effectively than you realise, or if he has friends coming to his rescue, footwork also takes you out of corto and into safety.

Footwork lets you control the range to your opponent to suit your goal. If your goal is to escape, you want to maintain distance at largo, identify a clear escape route, and run. If he tries to catch up, footwork helps you evade.

If your goal is to finish the threat, footwork places you in prime position to launch your attack. It puts you at the range and angle to employ your favourite techniques without exposing you to the enemy’s.

Against multiple opponents, mobility is critical. You cannot afford to slug it out with one guy. His buddies will flank you, slam you to the floor, and introduce you to the joys of a boot party. You need to keep moving to avoid being swarmed. This allows you to either exploit an opening to escape, or to maneuver yourself so that the threats get in each other’s way, allowing you to engage just one at a time.

Footwork and Angles

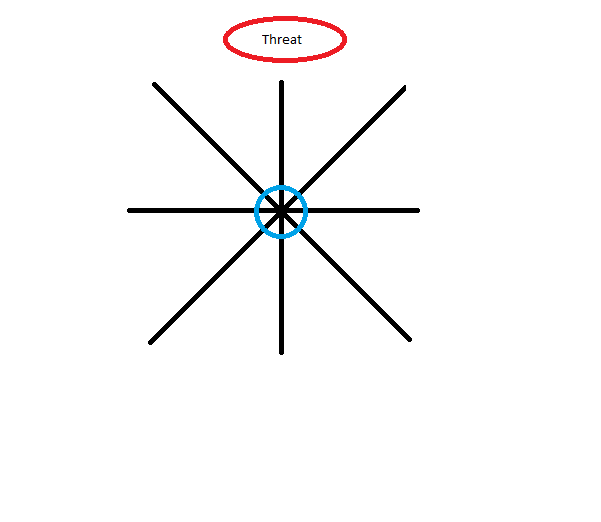

The second component of footwork is angles. Different styles have different approaches to controlling range and angles. FMA players use the analogy of a clock to describe angles of attack and movement. You can see this in the picture below.

You are the blue circle. The threat is the red oval. The lines indicate possible angles of movement. In front of you is 12 o’clock, where the threat is. He is in medio, advancing to strike you. As mentioned earlier, there are only three outcomes, and only one will go your way. You must get off the X and turn the situation around. There are four ways to do it.

The first method is to close in with a diagonal forward step. You step off on the 10 or 2 o’clock line, about 45 degrees off the line of attack. Other styles prefer the 11 or 1 o’clock, or 30 degrees. Combine this footwork with a turn towards the opponent. This places you on his flank. When the enemy sees you vanish from his 12, he needs to reorient towards you, buying you a precious moment to escape or to strike.

This is the preferred approach of PTK. PTK is an offensive-oriented art. This step places you in corto, giving you easy access to the threat’s head, throat, arms, side and legs. From here you can employ elbows, knees, stomps, traps, whatever you like. Other styles go one step deeper, circling around the threat to gain his back. From here, you can do whatever you like to him without fear of retaliation.

The second method is to step off with a diagonal rearward step (or leap). You move back on the 7 or 5 o’clock line (or 8 and 4), taking you to largo. This is not a permanent solution: a person can advance three times faster than he can move backwards. If you keep retreating like this the enemy will catch up and overwhelm you. This is a desperation move, to be employed only when you are surprised.

There are two main reasons to do this in PTK. The first is to buy you time and space to turn and run. The second is to stage a counterattack. For the latter, as you move, you take a piece of the enemy by striking at his hands while moving your body (and vital organs) out of the way. Then, with the enemy weakened, you can close into corto for the finish.

The third method is to sidestep to the 3 or 9 o’clock. This maintains the range between the two of you, but it puts you on his flank. If you have a long weapon like a stick or a staff, this lets you employ the weapon’s reach to the fullest; had you moved to corto, you would either have to give up the weapon’s advantages or employ different techniques. Further, if the opponent is bull-rushing you, this sidestep uses his momentum against him, either by giving you an opportunity to strike him before he can turn towards you, or to let him give his back to you.

The last method is the most dangerous: you move along the 12 or 6 o’clock line. You are still on the enemy’s angle of attack. But this may be your only option if you are attacked in a train, a bus or some other location where you have no room to maneuver.

If you go down the 12 o’clock, you are countercharging into corto range. This is the realm of clinches, infighting and takedowns. Once inside, there is little art here, just single-minded aggression and a desperate fury of elbows and knees, chokes and strangles, throws and takedowns. As the enemy can also do the same to you, you need to finish him off before he recovers–especially if he has a weapon.

Down the 6 o’clock, you encounter the same perils as the backward diagonal, with the added disadvantage of still being in the line of fire. Committing to retreating on the 6 o’clock is viable only if you are going to turn and run. If not, you need to use this move to set up a counterattack. When the enemy attacks, he is opening a line to his body. What you want to do is to step out into largo (ideally striking his hand), then counterstrike along the open line before he puts his guard back up. High-level players don’t even step; they just subtly sway or shift their bodies, just enough to take the target out of range, then lunge in on the counter. Floro Fighting Systems specialises in this method of countering a threat.

Notice how the players subtly sway and step back as the attack comes in, then immediately counter along the exposed line. This requires a superior sense of range and timing to pull off—but highly effective when done right.

Footwork and Fighting

Moving isn’t just about getting to safety: it powers your attack. Since you’re already burning all the calories to move your body, you might as well drive your bodyweight into the threat too.

FMA torques the hips to generate power. After completing a technique, the player is in a position that allows him to twist his hips and launch into another attack, which places him in a new position to strike yet again. This synergy is the basis of kali’s famous flow principle

For example, assume a threat is throwing a straight right punch. A kali player might crash in on the 10 o’clock line, slapping down the extended arm with his left hand and jabbing at the eyes with his right. As he retracts his right arm, he snatches the target’s arm and pulls it down. This clears the way for a left cross, a right uppercut and another left cross. Four blows in three seconds or less.

Different martial artists will have different responses. A silat player may step off-line on the 11 o’clock line and follow through with an ankle stomp, and if that doesn’t finish the job, he can whip around into a groin slap, then grip and rip. A boxer might slip the punch and shovel hook the threat’s side, then continue swarming him with punches. A judoka could attempt a throw, a Brazilian jiujitsu player might go for a takedown and a submission. But they all have one thing in common: they move off the line of attack, then use their new position to recapture the initiative.

Different styles have different methods of generating power through movement. Find the techniques that suit your body and personality best and see how your footwork can accelerate these techniques. Then drill incessantly to ingrain them.

Final Thoughts

Footwork is critical. For martial artists, proper footwork takes you out of danger and places the threat at risk of your most effective moves. For fiction creators, understanding footwork lets you choreograph exciting, dynamic fight scenes a cut above bog-standard Hollywood brawling. For gamers, proper footwork means you won’t bleed so much, especially in action RPGs.

Martial arts is about doing to the enemy without him doing the same to you. Footwork is how yo do this. If you are a martial artist – get on the mat and train.

Leave a Reply