I’ve always been a skeptic of the use of artificial intelligence in creative work, especially Large Language Models and art generators. An AI analyzes a prompt, gathers input, optimises data, and generates an output that attempts to satisfy the prompt. An AI does not create. An AI does not think. An AI does not know.

Where other authors have found success, or at least novelty, with AI, I cannot say the same for me. My style is singularly human—and therefore, singularly immune to machine intelligence. It rests upon a bedrock of deep research, first-hand experience and personal taste, none of which an AI possesses.

Nonetheless, I tried to give AI a fair shake. I booted up ChatGPT and and attempted to use it to craft fiction. The results were… instructive.

I began by instructing ChatGPT to write a scene. This was the prompt I used:

Write a fiction scene in which a Shaolin monk suddenly attains Enlightenment while practicing Xin Yi Ba.

The following is ChatGPT’s output, interspaced with my comments.

In the tranquil courtyard of the Shaolin Temple, the morning sun cast gentle rays upon the practicing monks. Among them was Master Liang, a devoted disciple known for his unwavering dedication to the ancient art of Xin Yi Ba.

In the first sentence, we see a mistake. The Shaolin temple is a sprawling complex, with seven main halls, seven secondary halls, and multiple courtyards. There is no ‘the courtyard’.

The second sentence contains two mistakes. Every Shaolin monk adopts the surname Shi as part of his dharma name, in honour of Shakyamuni, the founder of Buddhism. Being a ‘Master’, the monk wouldn’t be called a ‘disciple’, except as a disciple of an even more senior master, who isn’t mentioned here.

Three mistakes in as many sentences, and this is just the first paragraph.

With fluid movements, Master Liang executed each stance with precision and grace, his body an embodiment of controlled power and harmony. Sweat glistened on his brow as he delved deeper into the essence of Xin Yi Ba, his mind focused solely on the present moment.

When practicing martial arts, one does not ‘execute’ a ‘stance’. A stance is a specific method of holding your body, in preparation for other movements. The art is in moving from stance to stance, which people commonly refer to as ‘technique’.

How do you ‘delve deeper’ into the essence of the art? For Xin Yi Ba, and the Xin Yi family in general, your mind, body and intention must be unified. There is no gap between them. When you will it, you act. This is the highest attainment of the martial arts. One does not simply focus ‘solely on the present moment’. Your mind must be empty, for in emptiness, it is free to go anywhere. Being free to go anywhere, it fills everywhere.

This is the mystery and the secret of ‘Enlightenment’.

As Master Liang continued his practice, a profound sense of tranquility washed over him. His breath became steady, and his movements flowed effortlessly as if guided by an unseen force. In that moment, time seemed to stand still, and the boundaries between the physical and spiritual worlds blurred.

The first line is the first error-free line in the entire scene so far. Then the rest of the paragraph falls apart.

In the Xin Yi family, movement is not ‘guided by an unseen force’. It is guided by intention. You hold your intention, a very slight preference for something to happen—and then it happens. It is as if your body is moving on its own, but in reality, it is guided by your intent. This is a subtle phenomenon that can only be properly understood after years of diligent practice and first-hand experience, neither of which ChatGPT possesses.

Traditional Chinese philosophy—and the philosophy of many other ancient civilizations—do not draw as sharp a distinction between the physical and spiritual worlds as modern society does. The modern idea that the physical and the metaphysical are separate is an aberration, first popularised during the (Western) Enlightenment.

Xin Yi Ba is the highest Shaolin art, and Shaolin practices Chan Buddhism and martial arts as one. One of the key ideas of Buddhism is non-dualism. It is the recognition that there is no separation between self and other, one and two. There is no blurring between worlds, so much as a sudden recognition that there is no separation between them.

Suddenly, a surge of energy coursed through Master Liang’s being, enveloping him in a radiant aura of light. His senses heightened, and he felt a profound connection to the universe, as if he were one with all creation.

This scene might make sense—if the monk were practicing a Daoist art. An art that emphasises the cultivation of qi, or subtle energy.

Xin Yi Ba is a Buddhist martial art. While I don’t doubt there is a qigong component, most Shaolin arts in general don’t emphasise qigong the way a Daoist art would. The main focus of practice is unity of mind, body and spirit. Unity of qi happens to occur along the way.

There won’t be a sudden ‘surge of energy’ that ‘envelopes [him] in radiant light’. It is more like the dropping of a veil, and a sudden recognition of the interconnectedness of all things.

In that transcendent moment, Master Liang attained Enlightenment. The wisdom of the ages flooded his consciousness, revealing the true nature of existence and the interconnectedness of all things. He saw beyond the illusions of ego and desire, embracing the eternal truth that had eluded him for so long.

These statements imply that Enlightenment is an external phenomenon. It isn’t. It’s an internal realisation. It comes not by someone or something pumping in wisdom into your brain, but by you shedding everything that prevents you from perceiving the entirety of the universe.

In Buddhist teachings, you don’t ‘see beyond’ the illusions of ego and desire. You simply snuff out the unwholesome desires that lead to suffering. This is what Nirvana means: extinguishing the flame of desire, or separating the fire from its fuel.

With tears of joy streaming down his face, Master Liang sank to his knees in reverence, humbled by the magnitude of his realization. In that sacred moment, the echoes of ancient wisdom reverberated throughout the temple, touching the hearts and minds of all who bore witness.

The experience of Enlightenment isn’t that dramatic.

The Buddha described it as waking up from a dream. Interviews with others who have achieved such a state indicate serenity, calm, joy, confidence, clarity.

You’re not going to get there if you are fixated on the idea of an individual ego called “you” attaining this superordinary state called “Enlightenment”.

Not only that, it is not a magical moment. Attaining Enlightenment does not suddenly cause the teachings to spread to everyone around you. If it were that simple, Shakyamuni wouldn’t have had to travel across India. He could simply have sat under the Bodhi tree and enlightened everyone in the vicinity. Someone attaining enlightenment does not cause the teachings to “‘touch the hearts and minds of all who bore witness”, because it is an individual apocalypse, a revelation that reconnects the experiencer to the experience—no one else who is not also undergoing the same event. For the unattuned, they may not even realise that someone sitting next to them has suddenly gained Enlightenment.

From that day forth, Master Liang became a beacon of light and wisdom, guiding his fellow monks on the path to Enlightenment. Though his journey had been long and arduous, it was now illuminated by the radiant glow of inner peace and spiritual fulfillment. And as he continued to practice Xin Yi Ba, he knew that his quest for truth had only just begun.

Before Enlightenment, chop wood, carry water. After Enlightenment, chop wood, carry water. This Zen saying tells us that there is no outward difference between pre- and post-Enlightenment life. You still have to do the chores. You still have to live your life. The only difference is how you perceive things—and that changes everything you do.

Enlightenment isn’t some grandiose event. It doesn’t literally transform someone into a beacon of light, though I would accept it as a metaphor for the master taking on a teaching role to guide his fellow monks. But as a master, he would already be doing it. The only difference is that now he has first-hand experience of what he is trying to teach.

A journey ‘illuminated by the radiant glow of inner peace and spiritual fulfillment’ doesn’t make sense. The clause is best used to describe the master, not his journey.

Having attained Enlightenment and ‘spiritual fulfilment’, how is it that the ‘quest for truth had only just begun’? Buddhism uses the metaphor of the raft and the river to describe itself. You wish to cross a river, so you build a raft. The raft is Buddhism. When you reach the distant shore, you leave the raft behind. Having attained what you set out to achieve, there is nothing left to do.

The ‘quest’ of Buddhism, if you could call it that, is to discover what is already within you. So the phrase ‘quest for truth has only just begun’ makes no sense in this context. It might make sense for, say, someone who has recently attained a black belt in a martial art, because only now does he have the knowledge to put all the individual pieces of his art together and express them his way. It doesn’t make sense for someone who has attained Enlightenment.

In this little experiment, ChatGPT averages one mistake per line. Nothing of what I have written above is a secret or esoteric teaching. It’s all drawn entirely from open source information. This tells me that ChatGPT cannot judge the quality of the data it draws from to generate its input. It takes a human to do this.

In theory, an author can use ChatGPT to create a book within a day, then revise the manuscript to clean up the mistakes. But with performance like this, it is much easier and faster for me to write the book myself than to rely on ChatGPT to do the heavy lifting.

Some other author might be satisfied with an AI-generated manuscript and push it to the market immediately. Not me. I have higher standards, and so does my audience.

At this time, ChatGPT’s greatest contribution to the creative arts is to set a floor for minimum acceptable quality. A low floor, perhaps, but a floor nonetheless. As AI tools percolate, those who do not meet that floor may use AI to compensate. But for those who stand above AI, using it will only be a waste of time and energy. It is far better to emphasise the inherent humanity of your work, instead of resting on the fruits of unthinking machines.

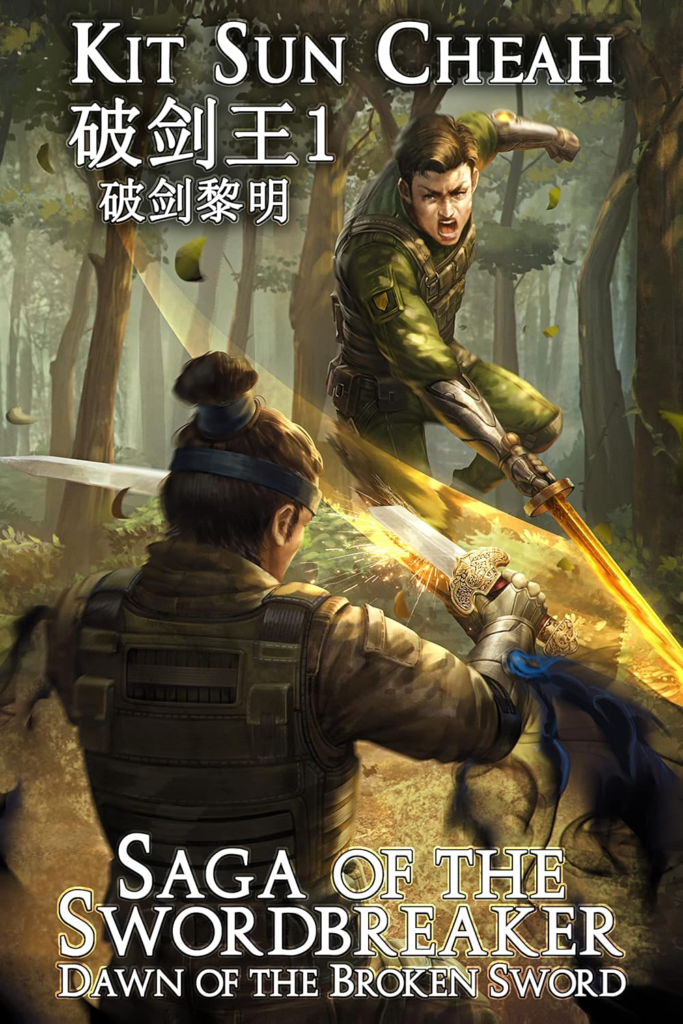

ChatGPT would never be able to write anything like Saga of the Swordbreaker.

Leave a Reply