When one thinks of horror in the pulp age, the figure of H P Lovecraft inevitably comes to mind. A doyen in the then-emerging field of weird fiction, he conceived of many modern horror tropes, and through his prodigious works brought to life the genre of cosmic horror. But another pulp giant also contributed immensely to the horror and weird fiction: Robert E Howard.

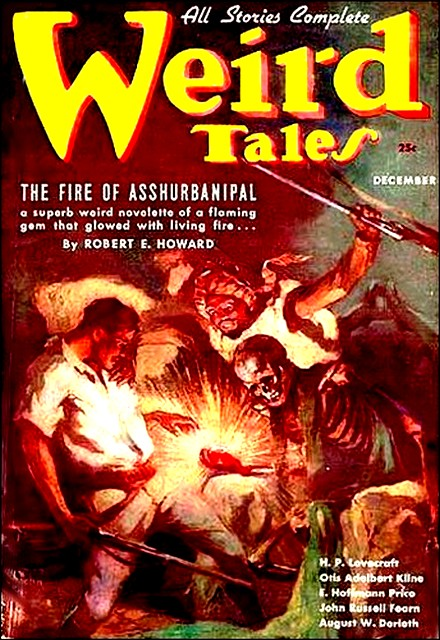

Hailed as literary geniuses and masters of the craft, Howard and Lovecraft were contemporaries who contributed to some of the same publications. They struck up a correspondence, discussing everything from politics to religion to writing, and exchanged ideas and themes which echo on in their works. Indeed, Howard set some of his horror stories within the Cthulhu Mythos, such as The Fire of Ashurbanipal.

Despite that, however, both men brought radically different worldviews to their writing. Lovecraft writes of the insignificance of man in an indifferent cosmos populated by unfathomable beings of immense powers, knowledge of which would surely shatter the mortal mind; Howard believes in a moral universe, where the strong, courageous and virtuous prevail over even the deadliest and foulest of eldritch abominations.

A Contrast in Style

Howard’s and Lovecraft’s styles are leagues apart. While both men enjoy the use of flowery language, Lovecraft much more than Howard, in every other respect their approach to storytelling is vastly different.

Lovecraft’s tales are broody at atmospheric. His signature seas of purple prose, describing in minute detail every character, object or location of interest, would be mind-numbing tedium had they flowed from the pen of a lesser write. But his phenomenal grasp of cadence, vocabulary, and most of all psychology transforms mere exposition into unseen literary hooks, sinking deep into the reader’s soul and pulling him along.

The length, density and complexity of Lovecraft’s prose keeps the story crawling along at a snail’s pace, forcing the reader to soak in every last detail. It also anchors the reader in what the narrator believes is ordinary lived reality, be it a sleepy fishing town in New England or a geological expedition to Antarctica. Little by little, Lovecraft drip-feeds small details of the horror inhabiting the story, gnawing bit by bit at the psyche of the protagonist and the reader. Then, when the moment is right, Lovecraft lets loose a vigorous torrential storm of sesquipedalian language, marking the final spiralling descent into the mind-shattering abyss.

Lovecraft’s style is uniquely suited for pure horror stories. He builds up the atmosphere, establishes the character and the setting, then mimics the sanity-shattering effects of whatever the character witnesses through the power of his prose alone.

Howard’s writing, in sharp contrast, is brisk, manly and dynamic. While certainly capable of literary fireworks, his emphasis is on relentless forward momentum. He describes just enough of the scene to allow the reader to picture it before driving on to the next. The reader doesn’t have to suffer through endless pages of exposition before something happens; in Howard’s stories, there is always something happening on every page.

This is the style of the pulp adventure. Written for the working public, conventional pulp stories are packed with action, adventure and excitement, transporting the reader from humdrum reality to fantastic lands were danger and glory waits behind every corner. Instead of slowly teasing out details before setting up a concluding apocalypse, Howard simply throws the reader headlong into the thick of things and rushes him through to a glorious, blood-soaked ending.

Is Howard’s style suited for a horror story?

It depends on the kind of horror story being written.

A Contrast in Character and Action

In Howard’s and Lovecraft’s works, the characters drive the plot. Yet both men wrote very different kinds of characters.

Lovecraft’s protagonists are usually passive and helpless, though there are some rare exceptions. Usually learned men, or born into cursed bloodlines, their story arcs have them slowly discovering a terrifying truth and either descending into delirium or accepting their destiny.

The horrors that populate Lovecraft’s stories are unfathomable alien creatures. With powers exceeding the comprehension of ordinary humans, they act according to their own agendas and morals, as unstoppable as gods. Some, as in the case of The Colour Out of Space, are impossible to define. Only a few have been defeated, but even then, they exact a punishing toll in blood and sanity.

Coupled with the heavy and oppressive mood, these elements combine to paint an image of a world forever teetering on the brink of conquest or annihilation. There is no hope, no respite, only bleakness and despair at the coming of the elder things.

Howard’s characters, by sharp contrast, are the epitome of masculinity. They aren’t soft and over-civilised males; they are warriors and adventurers and slayers, ready to charge into the teeth of Hell and cut down every demon in their paths.

Howard’s monsters are no less alien than Lovecraft’s, and indeed some of them have common characteristics. Solomon Kane confronts a powerful demon best described as a sentient shade of scarlet, while Conan has encountered a frog god that doesn’t seem to wholly occupy three-dimensional space.

However, where Lovecraft’s horrors are almost always too overwhelming to comprehend–much less kill–Howard’s monsters are almost always mortal. The beasts may be monstrous and powerful, but Howard’s heroes usually defeat the monster through raw strength, cunning, or sometimes with outside assistance. The monsters that aren’t defeated usually kill the villains of the piece instead, sparing the protagonist, as in The Fire of Ashurbanipal. Only rarely do the horrors destroy the protagonist.

Lovecraft’s passive yet intellectual characters and all-powerful horrors lead to slow-boiling stories, emphasising density of description and developing mood and atmosphere, building up to the final inescapable mind-blowing revelation. In contrast, the action-oriented heroes and mortal monsters that populate Howard’s works lend themselves to fast-paced, action-packed stories.

A Contrast in Morality

Through their stories, the pulp grandmasters created ethical frameworks that underpinned their worlds. Lovecraft and Howard are no different, and indeed their approach to ethics could not be more diametrically opposed.

Lovecraft’s most celebrated horror stories reject the concept of a morally-ordered universe governed by benevolent powers. There is no God to keep Cthulhu at bay, no flight of archangels to smite rampaging shuggoths. The horrors of his stories are either indifferent of or inimical to humanity, quite capable of snuffing out or subjugating the human race as easily as lifting a finger. The monsters operate by their own laws and reasoning, far removed from human experience and understanding. Humans are utterly insignificant, naked and vulnerable before the leviathans of the cosmos, and they can do nothing against the all-consuming void.

Howard’s stories, in sharp contrast, are grounded in a clear vision of good and evil. All of his characters, in one way or another, are heroic in their own right, be they pagan wanderers who slay their foes in honest combat, crusaders compelled to destroy all evil in sight, or lone gunmen bound by notions of loyalty and honour. Demonic and cosmic and eldritch horrors may exist, but all it takes is a single good man to defeat them.

Lovecraft’s stories are usually atheistic, or are otherwise filled with terrible alien entities with the powers of gods. There is no morality, no attempt to reach a state of enlightenment, no avenue for hope. Only the nigh-inevitable crushing collapse of sanity and humanity. Instead of aspiring to greatness or reinforcing the virtues of civilised society, Lovecraft instead expresses an uneasiness of humanity’s bumbling attempts at understanding the cosmos, unaware of the dangers and horrors waiting in the dark.

Howard’s stories use religious and pagan aesthetics as a framing device to highlight the clash of good and evil. Cairn in the Headland pits Christianity against pagan Norse worship, culminating in divine intervention; and Solomon Kane is unabashedly Christian in his outlook. Even characters without formal religion still have a sense of morals. In Worms of the Earth, a pagan king seeking vengeance on the Romans discovers how terrible the titular worms truly are, and vows never to use them again. Howard’s stories draw a sharp contrast between good and evil, and always strive to reinforce goodness.

Between Lovecraftian and Howardian Horror

Which style of horror is better? As with many things, it depends on personal taste. Indeed, you could even make the argument that most of Howard’s stories are not true horror stories at all, for they lack the elements of lingering dread, oppressive atmosphere, and personal vulnerability, trading them in for ultraviolent fight scenes.

What is clear is that these stories reflect something about the writers’ deepest selves. Howard grew up in the shadow of an oil boom and saw the seedy underbelly of society, and transformed himself from a weakling to a healthy man through daily physical labour. Lovecraft in turn was an autodidact in many subjects, considered himself an atheist, and grappled with mental health issues his entire life. These lived experiences are embedded deep in the fabric of their stories; their tales are, essentially, fragments of truth in fancy dress.

Regardless of your preferences, the aspiring pulp writer and student of the legendary Appendix N would do well to study the works of these grandmasters. Buried in their near-forgotten tomes, literary gems and terrible truths await the reader brave enough to find then.

—

My personal preference is Howardian-style action adventure stories, with a heavy dose of fantasy and a smattering of horror. If you like stories like that too, check out my latest novel HAMMER OF THE WITCHES.

To stay updated on my latest stories, news and promotions, sign up for my mailing list here.

Leave a Reply